7 Fundamental causes of growth

Karl Marx wrote in ``The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte’’:

“Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”

The Solow model relates growth to features of economies like their degree of saving or human capital. But why do some countries save more than others? Why do certain countries choose more or less efficient methods of organizing production?

This last question is probably the most critical. We call productivity as a “residual” - what’s left over after physical and human capital are accounted for. The fact that productivity is so highly correlated with GDP per worker (and person!) is evidence that that the proximate causes of growth - inputs and their direct determinants like savings rates - are not enough to answer the question “why are some countries richer than others?” We need to look for fundamental causes - things that explain productivity and investment in physical and human capital.

The economist Daron Acemoglu (who, along with his coauthors Simon Johnson and James Robnson, won the Economics Nobel Prize in 2024 for contributions to the study of economic growth) has sorted theories of growth into three big categories: geography, culture, and institutions. In addition to these, we might add another possible candidate – “policy.” We’ll briefly explore each, although we’ve already seen examples of those big theories. (Fact 5 in the Data section). We’ll briefly discuss some representative arguments in favor of each.

7.1 Geography

Geography is a catch-all term for the “exogenous” features of the physical environment. For example, climate and soil quality a country can affect agricultural growth. Ease of transportation on waterways – like rivers or oceans – can facilitate economic exchange, and coastal countries tend to be richer than landlocked ones. Swampier regions tend to have more diseases like malaria that affect health directly and other aspects of human capital indirectly. Natural resources – like deposits of energy resources, primary metals, etc – have been quite important in shaping some countries’ economic and political development over time.

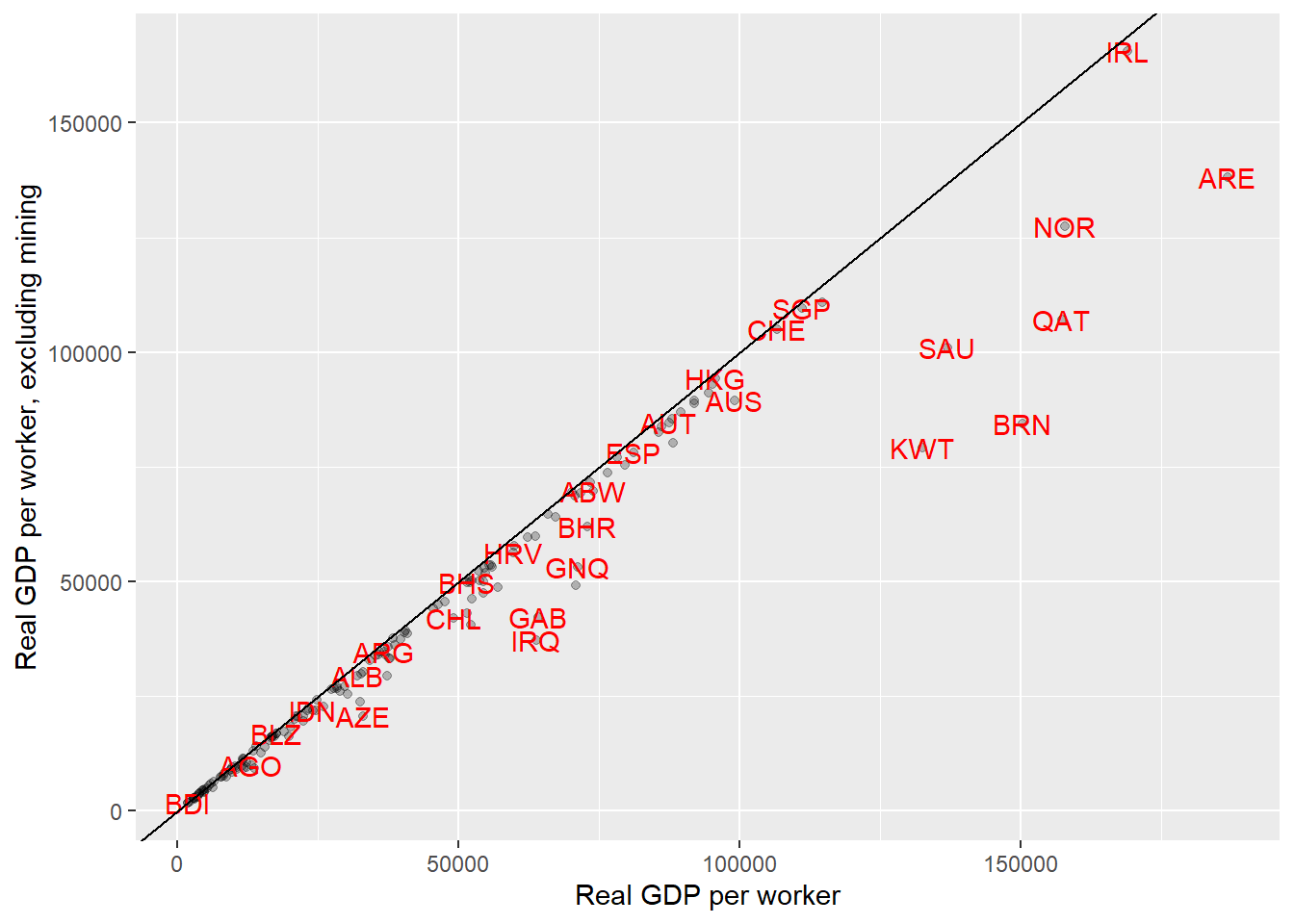

Although natural resources are only part of the overall geographic hypothesis, you might be wondering just how important they are. One, somewhat crude, way of looking at this would be to take real GDP and subtract the value added from the mining and resource extraction industry. (A similar adjustment was used by Robert Hall and Charles Jones in a widely cited paper from 1999). Below, I’ve plotted a scatter plot with real GDP/worker in 2017 on the horizontal axis and non-mining real GDP/worker on the vertical axis. Countries close to the 45 degree line have very little value added from mining. Countries further below the line have more of their GDP coming directly from the mining industry. You notice the big outliers are mainly oil-rich countries, which we saw are outliers in terms of GDP/worker (and in terms of having relatively autocratic institutions for rich countries, Norway excepted).

7.2 Culture

Cultural attitudes are persistent features of peoples’ beliefs, preferences, and attitudes. These preferences affect peoples’ economic choices at an individual level - for example, what sorts of jobs people choose (or whether they choose to work at all), and what sorts of transactions they engage in.

Religion is one facet of cultures that has often been theorized to affect economic outcomes. Max Weber’s assertion that the “Protestant Work Ethic” could explain disparate economic outcomes across European countries is one religious theory of economic growth.

There are more complicated theories linking religious beliefs to growth. For instance, countries with more developed financial systems might have higher savings rates because people can earn a return on saving. But religion can influence the development of financial systems; for instance, there were religious restrictions in Catholic countries that forbade lending at interest for many centuries (that variably applied to Catholics and non-Catholics), which may have affected the development of financial systems (and growth) in those countries. Today, many Islamic countries have different degrees to which lending at interest is illegal, and so-called “Islamic banking” systems exist to facilitate saving and investment using alternative arrangements to those in non-Islamic systems. The differences in religion may lead to differences in financial arrangements that affect saving, investment, and growth.

Religion, however, is not the only aspect of culture that might matter. For example, the economists Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Gérard Roland used data on cultural attitudes collected by sociologists across countries to characterize countries’ (average) attitudes along a “collectivist-individualist” axis. They argue that more individualist societies encourage innovation and discovery by socially rewarding individuals who stand out. Collectivist societies encourage conformity, which discourages innovation but may make it easier to solve “collective action” problems because individuals think about society’s interests when making choices. On balance, Gorodnichenko and Roland find that more individualist countries tend to have higher GDP per worker.

7.3 Institutions

“Institutions” is a broad category of features of social organization that affect (1) economic arrangements (property rights, barriers to entering markets) (2) political arrangements (constraints on politicians and elites). For example, property rights (the extent to which people control their property, and the ease with which that property can be legally or extra-legally taken from them) affect the incentives people have to acquire and use property. Institutions like the choice of legal system, constraints on executive authority, and the extent to which those constraints are effectively enforced can affect property rights.

Proponents of institutional theories often point to historical examples - such as the divergent outcomes of North and South Korea, East and West Germany, or communities on either side of the US-Mexico border - to support the case for institutions shaping economic growth. One such historical example economists have studied is the divergent effects of European colonization. Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson argued in an influential paper that colonizing powers set up two kinds of colonies: “Neo-Europes,” which were intended for permanent settlement by Europeans, and “extractive” colonies. The latter had institutions that facilitated taking wealth out of the country, and had few restrictions on executive power. The institutions they set up in the two kinds of colonies were persistent even after colonization ended. For example, the institutional setup in the United States and Kenya were quite different, despite both being British colonies. Acemoglu et. al. argue that the differences in colonizing institutions have had a powerful causal effect on economic outcomes as a result.

7.4 What about policy?

Policy choices are related to institutional choices, but are more mutable. The typical story for institutions emphasizes long-standing, hard-to-change arrangements. On the other hand, some economists and policymakers have emphasized the importance of particular policy reforms that could help countries develop – for example, removing restrictions on particular markets. One set of such policies colloquially became known as the “Washington Consensus” which included smaller budget deficits, controlling inflation, tax reforms, and liberalization of financial markets and trade.8 It’s easy to understand the perceived attractiveness of the policy idea. For example given a widespread consensus in the economics profession that, for example, allowing trade with other countries is good, removing taxes on traded goods to encourage trade may seem like a logical way to boost growth.

The evidence on how effective these reforms were is mixed. The economist Dani Rodrik declared, in 2006, that

“Proponents and critics alike agree that the policies spawned by the Washington Consensus have not produced the desired results…it is fair to say that nobody really believes in the Washington Consensus anymore. The debate now is not over whether the Washington Consensus is dead or alive, but over what will replace it”

On the other hand, a 2019 working paper by the economist William Easterly reviewed recent evidence and said

“[…] there is a strong correlation between improvements in policy outcomes and changes in growth outcomes.”

The question of policy is also a question about correlation versus causality (as Easterly’s quote alludes to!). Countries may have good policies because they have good institutions, for example.

Summing up

Economists have searched for “fundamental” causes of macroeconomic growth. Three broad categories of theories emphasize geographic, cultural, and institutional fundamentals that generate the outcomes in long-run growth and the distribution of wealth across nations. Economists and policymakers also have debated whether, conditional on a country’s history and geographic features, whether policy reforms can result in higher growth.

Although there are partisans for each point of view (and the arguments between their proponents can be caustic), it’s probably worthwhile to think of each as having some ability to explain outcomes in different countries. Certainly, “institutional” theories are quite powerful for explaining certain cases (like the split between North and South Korea’s outcomes). But most economists who have tested these theories have found that each explanation has explanatory power even after controlling for the others.

Part of the difficulty in identifying a single fundamental cause is that each seems related. The line between culture and institutions can be somewhat fuzzy, for instance. The Nobel-prize winning economic historian Douglass North, in fact, defined institutions as “the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction.” We know that things we might call “culture” can influence (and are influenced in turn) by institutional environments. And Acemoglu, Robinson and Johnson’s theory of why certain colonies were set up the way they are is linked to the disease environment - a geographic feature of the country in question.

John Williamson, the coiner of the phrase “Washington Consensus,” has written a number of articles about what the term meant and how it was (mis)used by others.↩︎